Dubai: The creation of vaccines against COVID-19 has been a bioengineering feat setting a record in research, manufacture, approvals and administration.

So far, we know that at least five active vaccinations (DNA, RNA, Viral Vector, Viral Subunit, Live attenuated, Inactivated, Virus Like Particles, Split Virus Vaccines, Ribonucleo Protein vaccine) have been created. In the passive vaccination variety, the monoclonal, polyclonal anti-bodies, the Convalescent Plasma and mRNA induced antibodies vaccine are available.

As vaccines receive approval and many have proved to have between 85-95 per cent efficacy, there is a sense of cautious optimism in the healthcare community.

On Tuesday, December 8, UK citizen Margaret Keenan, 90, became the first person in the world to receive the Pfizer COVID-19 shot outside of the trial, even as Britain and the rest of the world prepare to get their citizens vaccinated.

Image Credit: AP

On December 9, the UAE officially registered the inactivated vaccine Sinopharm developed by the Beijing’s Institute of Biological Products. The world is in a ready position to beat the deadly Sars COV-2 virus.

On the flipside there are vaccine skeptics raising their voices, saying the speed at which the vaccine research was fast-tracked, phased trials accelerated and quick approvals for mass manufacture from FDA being sought, leaves little room for objective perspective and evaluation.

Will the vaccines provide a complete cover against COVID -19?

Speaking to Gulf News, Dr Sundar Elayaperumal, specialist microbiologist and chairperson of Infection control, Burjeel Hospital, Abu Dhabi explained: “We cannot expect complete eradication of COVID-19. The vaccines are going to be helpful in controlling the spread of the disease. They might not be 100 per cent efficacious, but will help the elderly, those with co-morbidities to have a stronger defense.

Combined with the naturally strong immunity in some, it holds out a strong hope in the battle against COVID-19 which is here to stay for some time.”

Dr Elayaperumal added that as the world was currently going through a second wave of infection it was evident that the virus had turned less virulent. “In the second wave, more people are asymptomatic; there is lesser dependence on ventilators and lower incidence of mortality reported. In the next few years we will have to depend on the current protocols of wearing masks, social distancing along with the vaccination to be able to control and manage the situation.”

Vaccine as a best line of defense

Dr Atul Aundhekar, CEO of Avivo Health Care Group who has been closely following the vaccine trials said: “Whatever the vaccine detractors might say, history has been witness to the fact that we have successfully eradicated small pox, effectively controlled polio and a host of lethal disease by running an effective vaccine programmes. So far, there is very little data on how the new COVID-19 vaccines will work in case of pregnant women, those with thyroid and diabetes and other comorbidites.

However, even if the vaccines are able to provide 90 per cent cover against the deadly disease it will help us steal a march over the pandemic. The vaccine cannot cover all strains of the virus, there are bound to be several sub strains are likely to be left out.

However, if it helps our body produce anti-bodies against the basic sub-strains, we can be hopeful. There is little evidence for how long the vaccine will provide the cover and how many doses will be required annually. This is work in progress. We have broken ground now and the next few years will be very crucial.”

Goal of a vaccine

Gulf News also spoke to a few specialists from Mayo Clinic Network, USA. Actively spearheading vaccine research and development Mayo Clinic has put together a Sars 2 COVID Research Task Force that has been conducting research on the virus, on immunology and studies on vaccines aided by artificer al intelligence analytics to compute outcomes. Dr Andrew Badley, head of the COVID-19 task force and Dr Gregory Poland, Director of the Vaccine Research Group at Mayo Clinic, explained why vaccines held out a strong hope.

Dr Badley explained: “The goal of a vaccine is to do one of two things. To prevent an infection and to make an infection less severe. The way a vaccine achieves this is by creating an immune response that is specific to the virus.”

How vaccines work?

Elaborating on the mechanism, Dr Badley explained: “The vaccine triggers two kinds of immune responses that we are interested in. The first kind is producing antibodies. Antibodies are soluble and are present in plasma, and their job is to bind to the virus and neutralise it so it cannot infect a cell. The second kin d of immune response is production of T- cells. The goal of a T-cell in the context of an infection is to kill those cells that are infected, and those infected cells essentially become virus factories.”

The trials conducted for a vaccine in phases are double blind where some volunteers get the vaccine while another control group gets a placebo. “The hope is that those who get the vaccine get infected less frequently, and when they are infected, they get less sick. There are many unpredictable factors. It is important to have controlled observation of people who get the vaccine to see whether or not there are side effects that were unintended.”

However, all vaccines require post marketing surveillance to study the long- term impacts. The health care bodies will have to implement this in case of the COVID-19 vaccines.

Herd immunity

Dr Poland was skeptical as he felt the impact of the vaccine is likely to be felt only once a maximum number of people around the world get the vaccine, but there may be people who might refuse the vaccination. “If the vaccines truly 90 per cent effective across the population and everybody took it, then we’d reach herd immunity that may not happen as many might reject the vaccine. Besides, we still don’t know if the vaccine will be 90 percent effective when used outside the clinical trial.”

Vaccine distribution

The global battle against COVID-19 cannot be successful unless the world comes together. Recognising this imminent need, the WHO ratified, GAVI (Global Alliance for Vaccine and Immunisation) has formed the COVAX Pillar. Within it, it has promulgated ACT (Access to COVID-19 Tools) Accelerator. ACT is the global partnership among political leaders, public, private partners, academia and other stakeholders to ensure an equitable distribution of COVID-19 diagnostics, therapeutics and vaccines across the world. About 64 higher income economies have joined the COVAX facility, to ensure that the COVID-19 vaccines reach those in greatest need. The argument for this is that as long as anyone is at risk, no one can be safe.

Catch me if you can: Vaccines and virus strains

Jaya Chandran, Online Editor

As the deadly virus spread the world killing more than 1.5 million people the only hope for the humankind was discovery of a vaccine at the earliest. But that was not easy. The delay in finalizing a vaccine soon gave rise to another fear. Has the global spread enabled the virus to mutate to different strains? Will it now be able to contain the virus with just one vaccine?

So far, the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 has mutated into seven major groups, or strains, as it adapted to its human hosts.

Mapping and understanding those changes to the virus is crucial to developing strategies to combat the COVID-19 disease.

“The reason for looking at the genomics is to try and find out where it came from in terms of trying to map out what we would expect for the pandemic, which information is critical,” South Australia’s chief health officer, Nicola Spurrier, said following an outbreak in the state in early November, Reuters reports.

The new agency has analysed over 185,000 genome samples from the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID), the largest database of novel coronavirus genome sequences in the world, to show how the global dominance of major strains has shifted over time.

The original strain, detected in Chinas Wuhan city in December 2019, is the L strain. The virus then mutated into the S strain at the beginning of 2020. That was followed by V and G strains. Strain G mutated yet further into strains GR, GH and GV. Several other infrequent mutations were collectively grouped together as strain O.

Why mutations matter: Are we too late already?

A mutation is a change in an organism’s genetic material. When a virus makes millions of copies of itself and moves from host to host, not every copy is identical. These small mutations accumulate as the virus is passed on and copied again and again.

The most recent mutation to emerge is the GV strain, which has so far been isolated to Europe where experts say it is unclear whether the strain is spreading because of any transmission advantage or because it affected socially active young adults and tourists over the summer.

The SARS-CoV-2 virus has so far mutated slowly, allowing scientists and policy makers to keep on top of its progress.

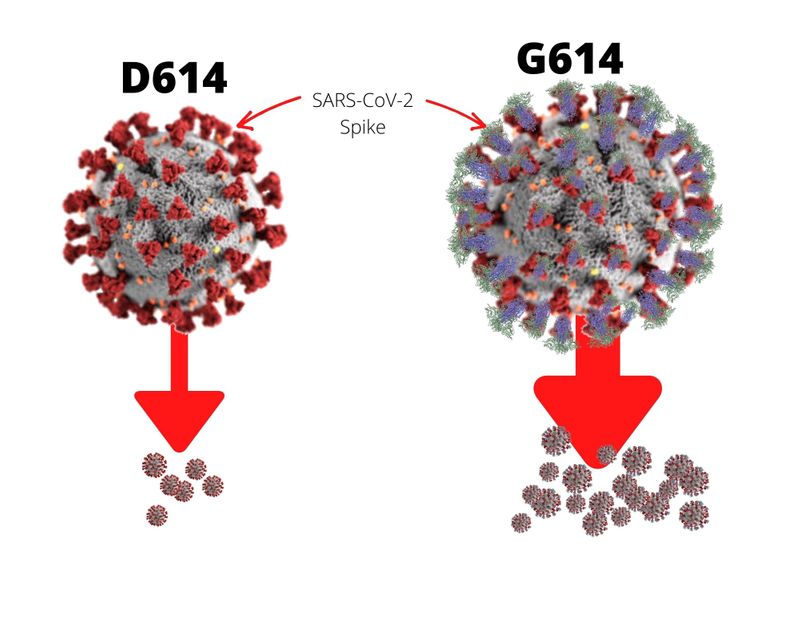

Still, scientists have been divided on the implications of some of the mutations. Some experts have reported that the D614G variation has made the virus more transmissible, however other studies have contradicted that.

Either way, the changes so far have not resulted in strains that would likely be resistant to vaccines in development.

However, experts who have watched influenza and HIV mutate over years, evading vaccines, warn that future mutations of SARS-CoV-2 remain unknown. And the best shot at avoiding changes that make the virus impervious to a vaccine remains curtailing its spread and reducing the opportunities it has to mutate.

If the virus changes substantially, particularly the spike proteins, then it might escape a vaccine. That is one of the reasons why scientist want to slow down transmission globally.

[With inputs from agencies]